Makers and Retailers

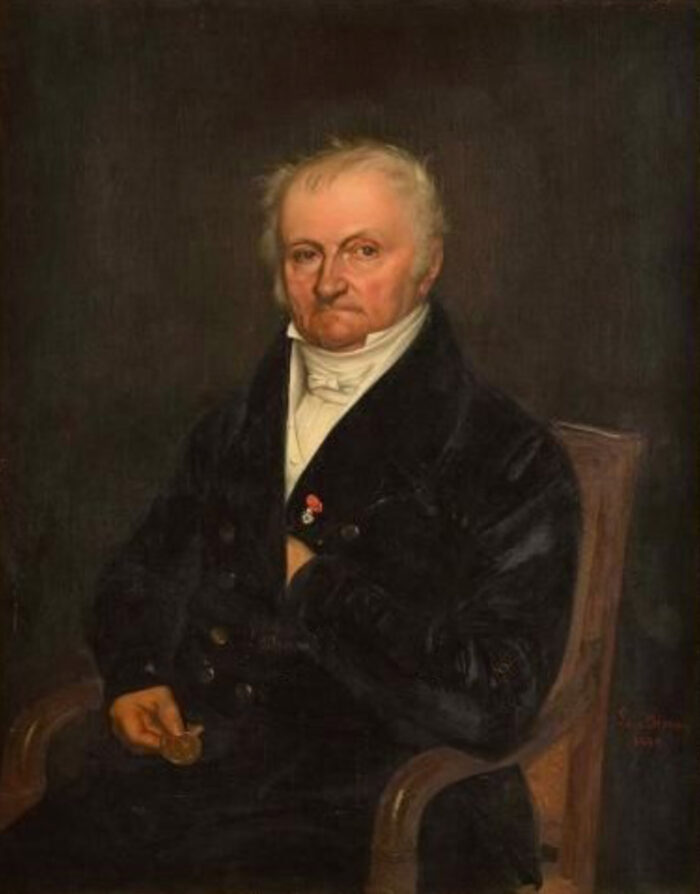

Martin-Guillaume Biennais

Martin-Guillaume Biennais was born in the Normandy region of La Cochère, France in 1764. His early years were dedicated to training as a craftsman, before moving to Paris at the age of 24. There, he specialised as a tabletier (a manufacturer of small luxury and decorative items from wood and/ or ivory), an ébéniste (a cabinet-maker, particularly working with Ebony) and an orfévre (a goldsmith).

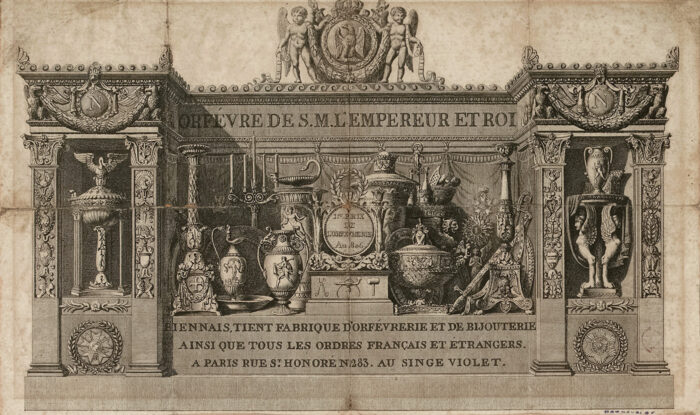

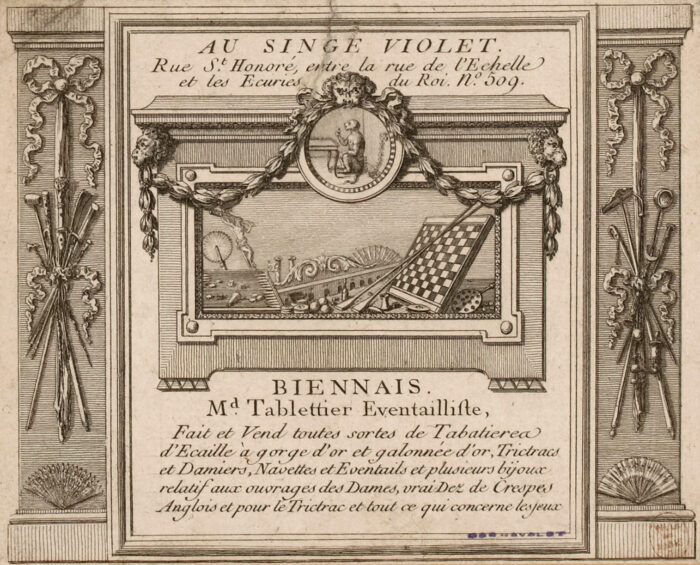

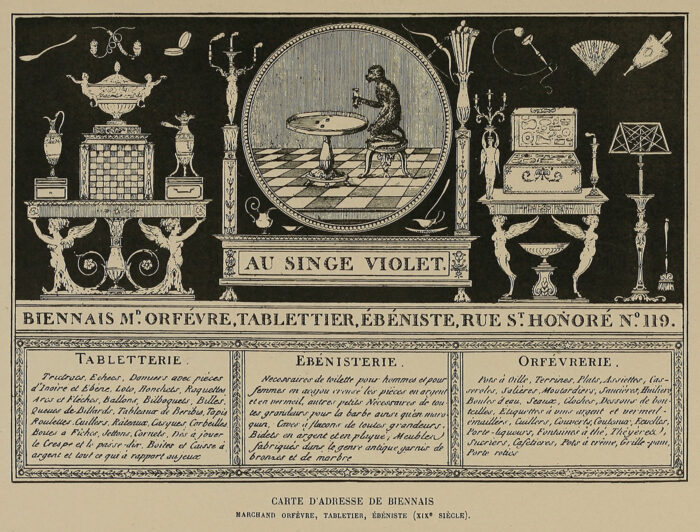

In 1789, Biennais set up his own establishment at Au Singe Violet (at the [sign of the] purple monkey), 509, 510 & 511 Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris. In 1790 the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 Rue Saint-Honoré, then changed again in 1805 to 281 & 283 Rue Saint-Honoré.

One of Biennais’ particular specialities was the manufacture of travelling nécessaire boxes, often crafted from solid mahogany; he employed freelance silversmiths to populate their interiors with bottles, jars and all manner of ‘necessary’ tools and instrumentation to accompany their owners during travel. At this time, the demand for luxury goods was very minimal, but Biennais’ work supplying nécessaires to French army officers reliably sustained his business. With the dissolution of worker’s guilds and associations under the Le Chapelier Law of 1791, merchants and artisans were now allowed to work as individuals free from their former practice restraints; as a result, Biennais expanded his business repertoire by being able to manufacture and certify silver items in-house.

In 1798, just prior to Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to Egypt and Syria, Biennais supplied Napoleon with some nécessaires on credit with the agreement that the debt was to be repaid upon his return. As good as his word, Napoleon did indeed pay what he owed. Whilst the work of Biennais was exceptional and spoke for itself in its own right, it seems that the faith and trust he exhibited towards Napoleon also favoured him well; in 1804, Biennais was made the imperial goldsmith, supplying the crown, sceptre and other ceremonial adornments for Napoleon’s coronation in December of that same year.

At the height of his success, having built up an exclusive client base to include the French imperial and royal family, the King and Queen of Holland, the King of Westphalia, and the royal households of Russia, Austria and Bavaria, Biennais was employing nearly 200 artisanal workers.

In 1819, Biennais retired, leaving his business to his former apprentice, Jean-Charles Cahier.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais died at his home in Paris in 1843 at the age of seventy-eight.

Today, the magnificent works of Biennais are rare, but can be found in some of the most renowned museums, royal households, stately homes and private collections around the world.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764-1843).

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1811.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1805.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertisement/ letterhead from 1789 within his first year of business. Note the address number of 509; the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 in 1790, so we are able to accurately date this.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertising business card from circa 1795.

F. L Hausburg

Friedrich Ludwig Hausburg was born in Berlin, Prussia in 1817. He began his career working alongside his uncle, August Wilhelm Bernhardt Promoli, based at 4 Rue de Boulogne, Paris, specialising in fine jewellery, clocks and a wealth of other luxury items.

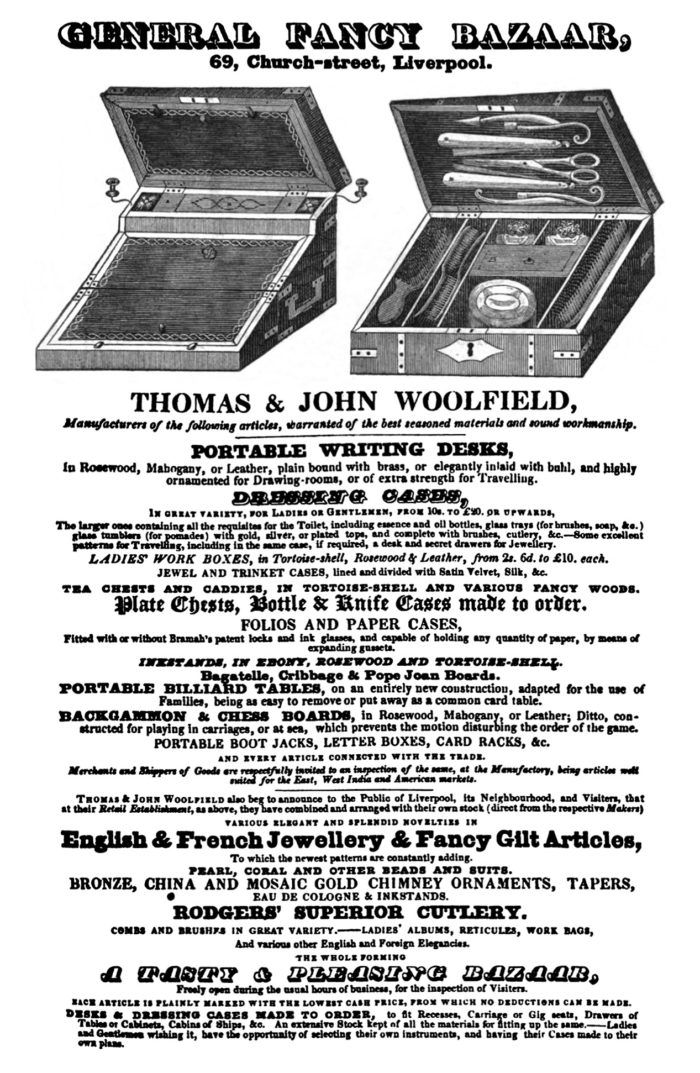

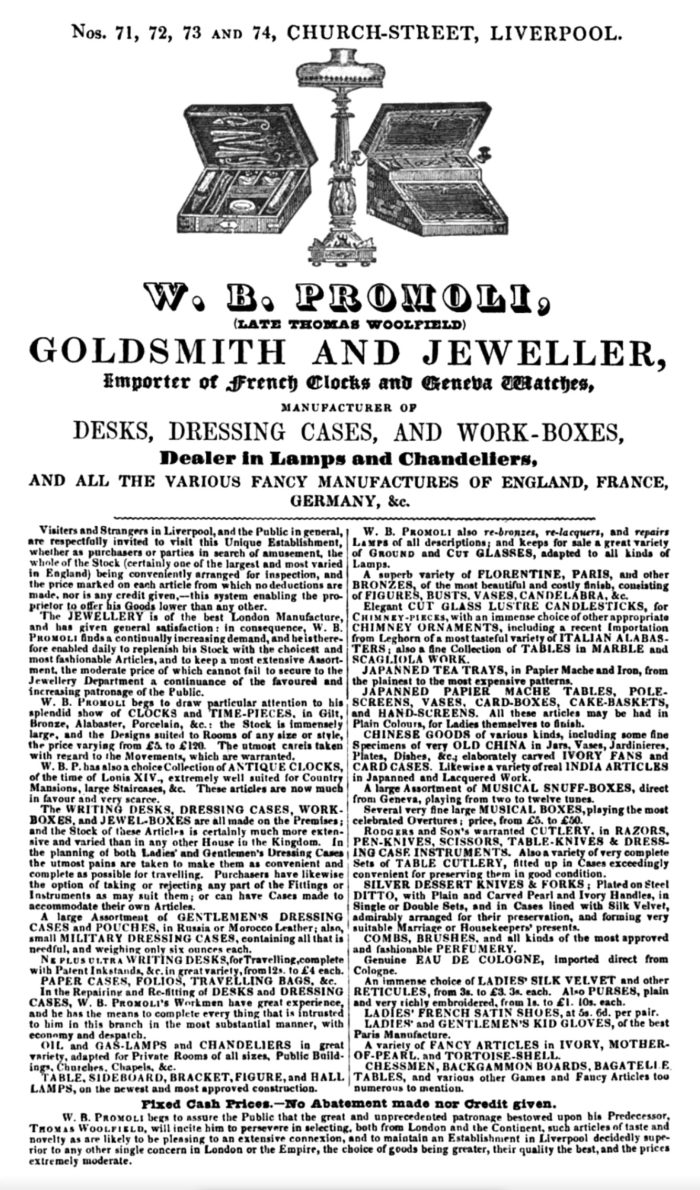

An advertisement from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory confirms that Promoli had taken over the business of Thomas Woolfield by 1837. Woolfield was the uncle, by marriage, of Hausburg’s wife, Catherine Mossop; he was predominantly a writing and dressing case manufacturer, but also retailed a vast array of fancy goods. Having been previously known as Woolfield’s Bazaar, based at 71 & 72 Church Street, Liverpool, the business was now titled as W. B Promoli and had expanded to 71, 72, 73 & 74 Church Street.

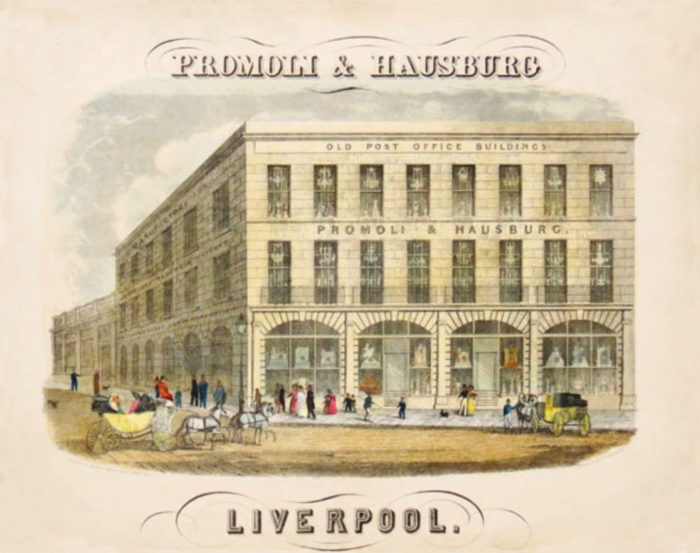

In August 1840, both Hausburg and Promoli were naturalised as British citizens; a legal act that could not only boast having Queen Victoria as its personal signatory but that, uniquely, was passed in just five weeks instead of a usual four years. That same year the name of the business was changed to Promoli & Hausburg, with their address now declared as Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool. Together, they advertised themselves as ‘Jewellers, Watchmakers, Manufacturer’s of Desks, Dressing Cases, Lamps and Chandeliers’.

Just a year later in 1841, the business was solely in the hands of Hausburg who continued dealing in the same vast range of luxurious inventory.

Looking at Hausburg’s work, one can clearly see the French influences harking back from when he was working in Paris; whilst very well versed in the more ‘reserved’ British style of exterior case design, he often produced pieces that featured far more lavish and intricate inlay work. Hausburg was known to use materials such as brass, pewter, ivory, abalone and mother of pearl to inlay into woods, or produce pieces dressed with Boulle work (tortoiseshell inlaid with brass). These decorative influences were often also applied to the interiors of his cases, with the inclusion of elaborately gold tooled leather to line the walls, floors, trays, and other components.

Hausburg retired in 1860 at the age of 43, selling his business to W.H Tooke who continued it from the same address. When Hausburg died in 1886, his estate was valued at a staggering £180,000 (£24 million in today’s money).

There is a wonderful, if not a little manic, article entitled ‘A Fashionable Shop At Liverpool’ written by a New York journalist, taken from the The Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review – June 1849, Vol. XX, No. VI; this journalist is in a state of rapture and trying, or rather struggling, to accurately make sense to his readers [and, I must assume, himself] just exactly what he has experienced after having visited Hausburg’s establishment,

“It must not for a moment be confounded with those receptacles of low-priced and slop-manufactured articles, commonly called bazaars, where there is much glitter and show, much tinsel and gay color, but little solid and substantial value. Presenting infinitely more variety than the best or more extensive of the marts just alluded to, it ranks above them in a degree that will not admit of the slightest comparison in the richness, rarity, beauty, and we may, with propriety, say splendor, of the articles offered for inspection. Indeed, I should not have written the word bazaar in connection with it but for the purpose of preventing any mistake or comparison of ideas in the mind of my readers. It bears about the same relation to a bazaar that a costly jewel, tastefully mounted in fine gold, does to a glittering gewgaw of paste set in Dutch metal. It wants an appropriate designation, for it is so completely unique that no ordinary term will serve to convey to the mind any notion of its extent, appearance, or purposes. I cannot call it a shop or a store without conveying an inappropriate image or false impression.I have seen the magnificent shops of London and Paris, and there are some fine shops, too, in Liverpool, but this establishment is so entirely different from them that the designation would be utterly inappropriate. As to ordinary shops, it is as infinitely superior to them as a palace is to a cottage.“

An Illustration from 1840 of Promoli & Hausburg’s emporium, manufactory and warehouse based at Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool.

F. L Hausburg manufacturer’s mark gold tooled onto leather from an 1852 antique dressing case in burr walnut.

Thomas & John Woolfield advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1828-9.

W. B Promoli (late Thomas Woolfield) advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1837.

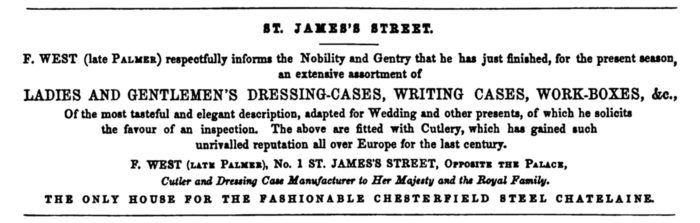

F. West

Fitzmaurice West established himself as a cutler and dressing case manufacturer in 1839. It is likely that West was a former employee of George Palmer, also a cutler and dressing case manufacturer, and they shared a premises based at 1 St James’s Street, London. Although Palmer continued working at this address until at least 1842, records and advertisements from 1840 show that West declared his business as ‘late Palmer’; this would indicate that although they were still sharing an address, they were now two separate businesses.

West became one of the appointed manufacturers to Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the Duchess of Kent and other members of the Royal Family.

West exhibited his dressing cases, writing cases and travelling bags at the International Exhibition of 1862. Along with fellow dressing case manufacturer Charles Bazin, West was on the panel of jurors for the International Exhibition presiding over the category of ‘Dressing Cases, Despatch Boxes and Travelling Cases’. This position precluded West from having his own exhibits judged, however the following was documented in the ‘International Exhibition 1862 – Reports By The Juries On The Subjects In The Thirty-Six Classes Into Which The Exhibition Was Divided’ (Peter Le Neve FOSTER, John Frederick ISELIN (the Elder) 1863), “The Jury consider it a duty to state their opinion with respect to the collections exhibited by Mr. F. West and Messrs. M. & B. [Mechi & Bazin], and to declare that, but for the exceptional and honourable position which they hold, they would have placed them in the first order of merit”.

West moved his business to 2 St James’s Street, London in 1877 and later, in 1883, to 9 King Street, St James’s, London.

As a side note, it is interesting to observe that many of West’s dressing cases were finished with ebony veneer and contrasted with brass work. This was a relatively unusual veneer choice for an English dressing case, and it is indeed possible that West was inspired by his French contemporaries, who often adopted this ebony and brass combination for their nécessaires.

F. West advertisement taken from The Stowe Catalogue, 1848.

‘F. West – Manufacturer To Prince Albert & The Royal Family – No.1 St James’s St.’ engraved brass manufacturer’s plate from an antique dressing case in coromandel with silver fittings, by Fitzmaurice West.

Mechi

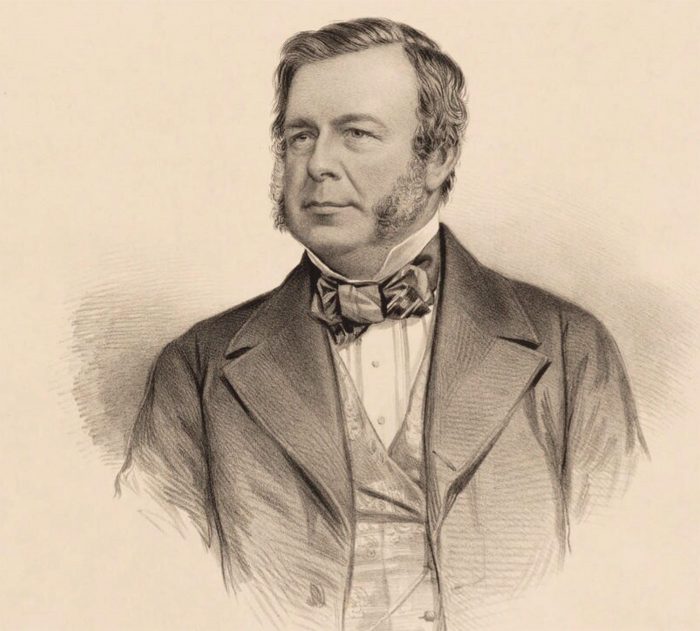

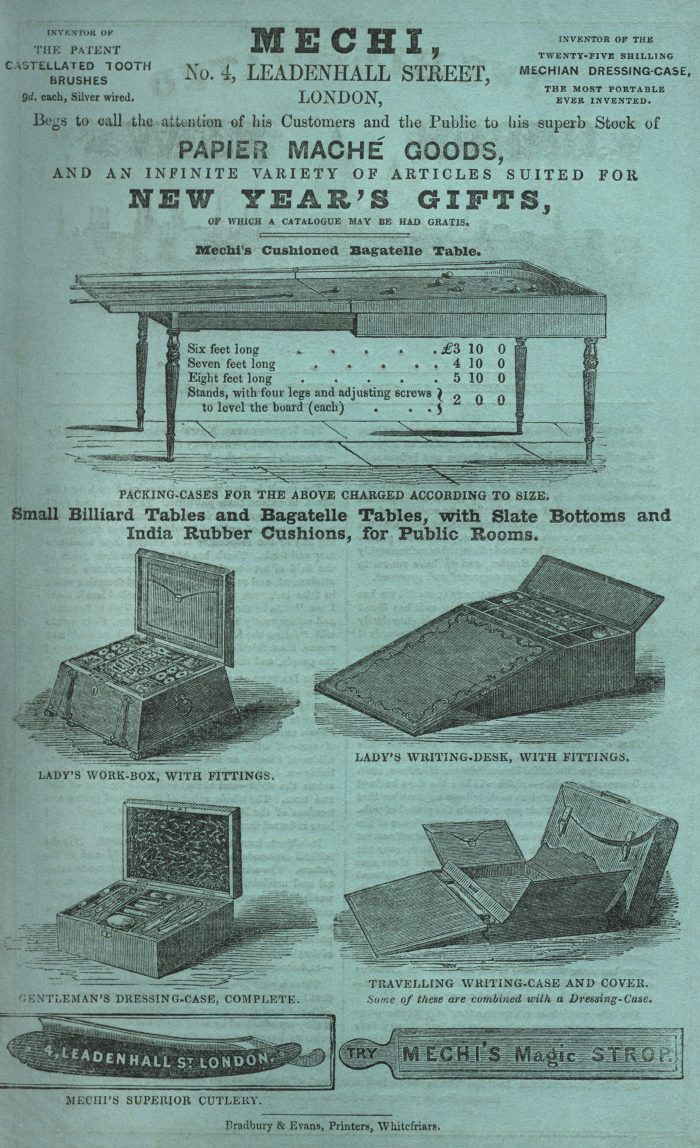

Of Italian descent, John Joseph Mechi was born in London in 1802. From savings amassed over a ten year period from his job as a clerk, in 1827 Mechi started his own business as a cutler from 130 Leadenhall Street in the City of London.

In 1830, he moved to a larger premises at 4 Leadenhall Street. Whilst Mechi manufactured a vast array of necessities and luxury items, his Magic Strop (an instrument to maintain and sharpen cutthroat razors) is what made him extremely successful and wealthy. Mechi was a master self-promoter, and his – often over-elaborately written – advertisements were prevalent in the English periodicals.

Despite being a very talented cutler his passion was for farming; in 1841 Mechi bought a large failing farmland estate in Essex which he rebuilt and, by applying his own advanced methods and techniques as well as a great deal of money, turned it into a model farm that he renamed Tiptree Hall. This became a very profitable enterprise and Mechi was soon renowned as an agricultural expert, publishing a significant amount of literature and demonstrating his practices and machinery for the many hundreds of visitors to his farm each year.

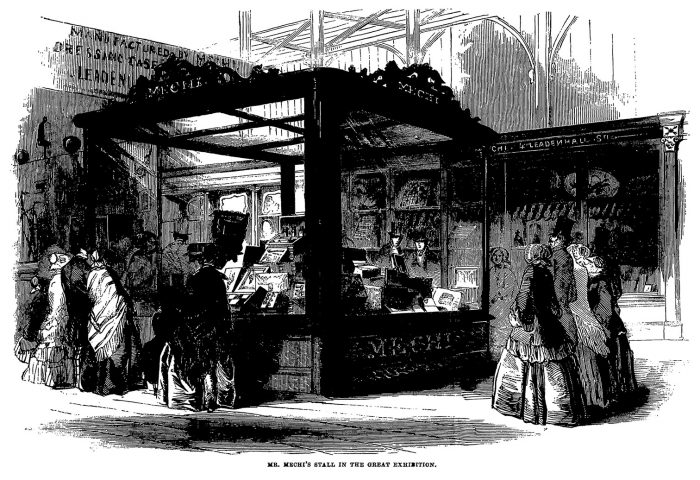

Through his membership of the Society of Arts, Mechi became a juror for the art and science department at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855. Although his duties precluded him from competing for awards at the Great Exhibition, Mechi displayed an assortment of his wares to great fanfare, including dressing and writing cases, work boxes and even a working model of his Tiptree farm.

Ironically Mechi’s fortunes were made and lost because of the beard. Up until the Crimean War (1854-56), the fashion for gentlemen was a clean-shaven appearance. Despite beards being banned in the army, the freezing temperatures experienced by the soldiers on the Crimean peninsula along with the inability to get shaving provisions negated this rule. Soldiers returning from war sporting their beards inspired a brand new and largely adopted fashion that was now synonymous with heroism. Mechi’s razors and ‘Magic Strops’ were no longer of interest and business plummeted with an almost immediate effect. The timing was particularly dire as Mechi had recently expanded his business in 1855 with further locations at 112 Regent Street, and at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. [The ‘Crystal Palace’ was the venue for the 1851 Great Exhibition, and was dismantled and rebuilt in Sydenham in 1854].

In 1856, Mechi became the governor of the Unity Joint Stock Mutual Banking Association as well as being appointed a Sheriff of the City of London. Moving up a rung on the political ladder, Mechi was elected as Alderman of Lime Street Ward, City of London in 1858.

Charles Bazin had worked with Mechi since 1838 and was a skilled cutler in his own right; for all intents and purposes he had single-handedly run the retail business whilst Mechi was turning his attention to his political career. In respect for Bazin’s twenty-one years of loyal support, Mechi made him a partner in the business in 1859; accordingly the business name changed to Mechi & Bazin.

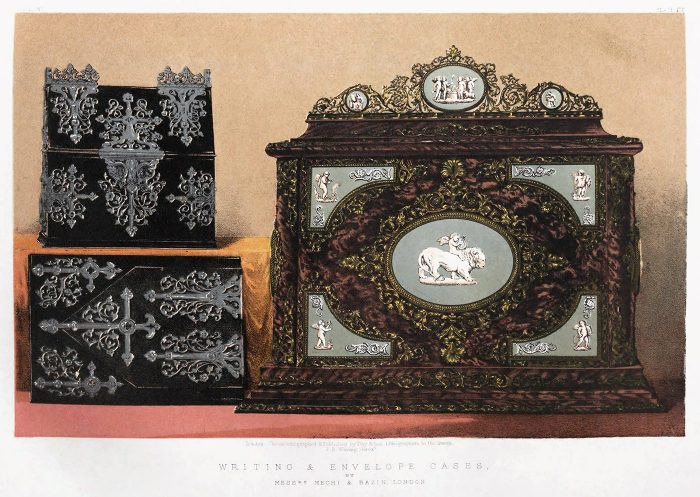

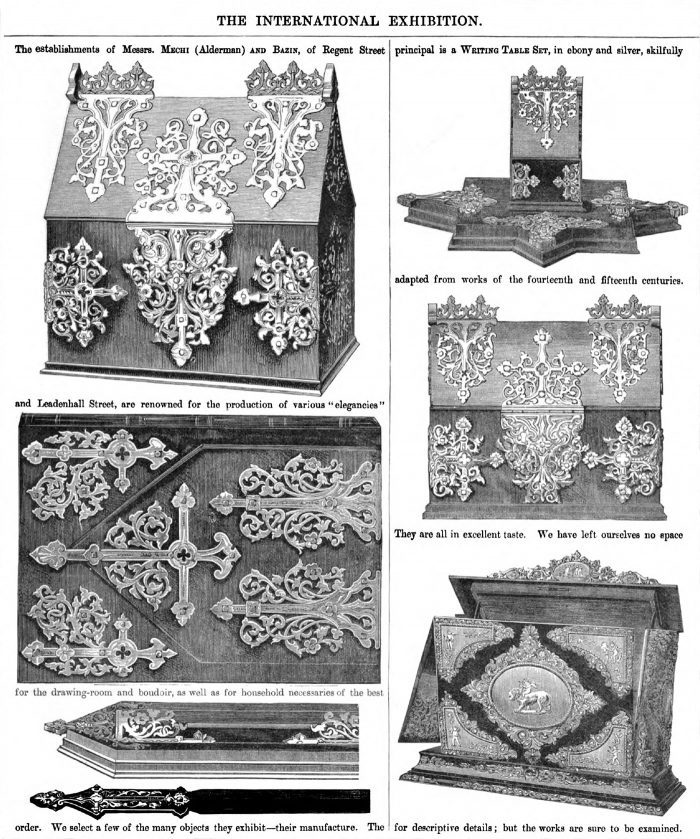

Mechi & Bazin displayed a selection of their dressing cases, despatch boxes and writing table sets at the International Exhibition of 1862. Due to Bazin being one of the jurors for the ‘Toilet, Travelling, and Miscellaneous Articles’ class, Mechi & Bazin were precluded from the award assessments.

When Charles Bazin died in 1865, at the age of 40, the ownership of the business transferred back to Mechi. The 4 Leadenhall Street location was closed and the entirety of the business was moved to his Regent Street address. However it wasn’t until 1869 that the name of Mechi & Bazin officially reverted to Mechi’s own.

Mechi was an extremely well-known, determined and relentless character; his past business failures had never meant the end, they merely signified a time for necessary reinvention. However his life and fortunes permanently changed with the collapse of the Unity Joint Stock Mutual Banking Association in 1866 for which he was found chiefly responsible. As a result, he lost £30,000 [approximately £3.4 million in today’s money] from his own coffers and felt compelled to resign from his Aldermanic post and from his running for Lord Mayor of London.

On the 14th December 1880, Mechi’s retail and farming businesses were put into liquidation, with Mechi, a now broken man, dying just 12 days later on Boxing Day.

John Joseph Mechi (1802-1880).

Illustration of Mechi’s shop at 4 Leadenhall Street, London taken from his catalogue entitled, ‘List of Articles Manufactured and Sold – Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation, by Mechi, No.4 Leadenhall Street, London.’

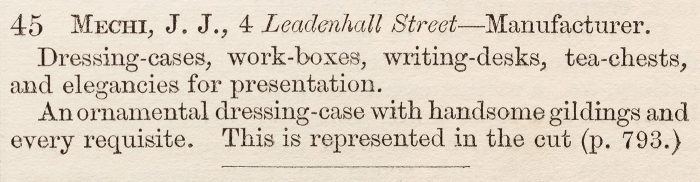

A Mechi advertisement taken from Charles Dickens’ serialised version of ‘Martin Chuzzlewit’ from January 1844.

An illustration of Mechi’s stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851 taken from the ‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851.

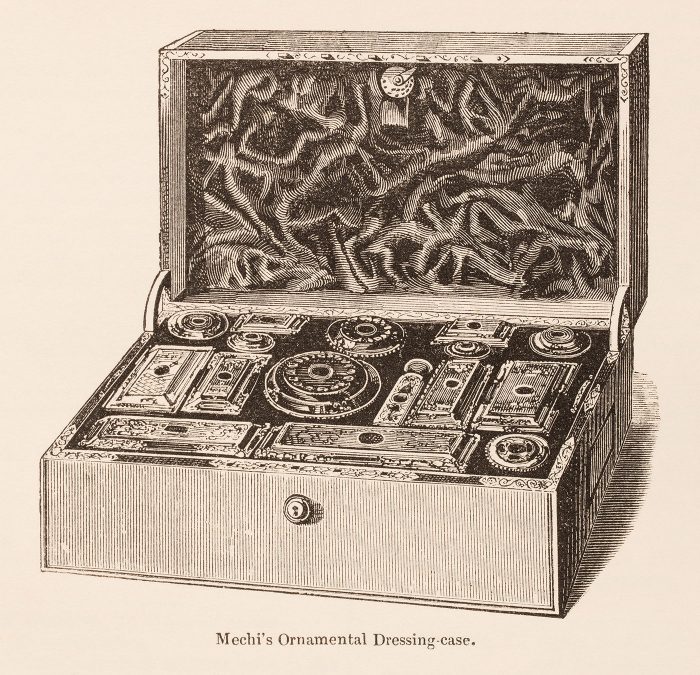

An illustration of Mechi’s ornamental dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A description of Mechi’s ornamental dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A Mechi advertisement taken from Charles Dickens’ serialised version of ‘Bleak House’ from March 1852.

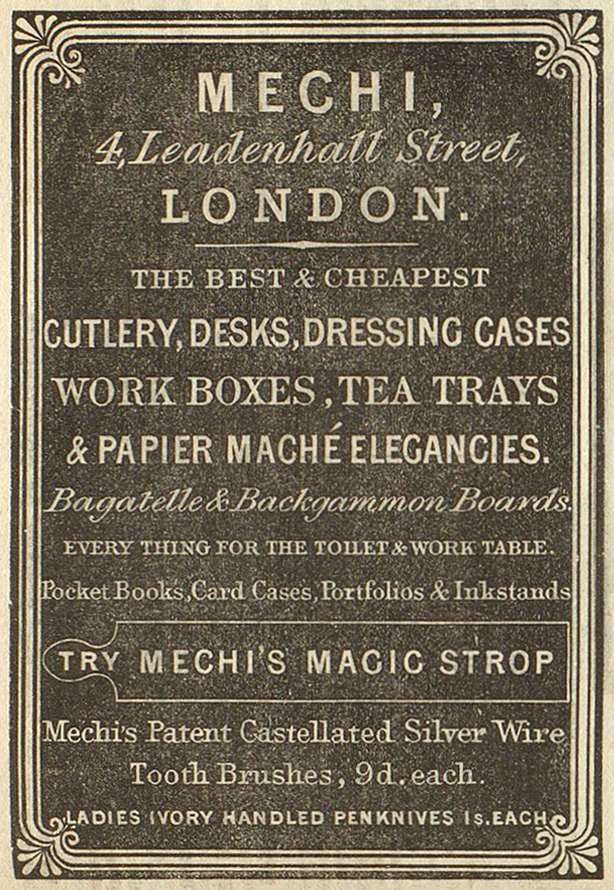

A Mechi & Bazin advertisement taken from the ‘International Exhibition 1862 Official Catalogue of the Fine Art Department’.

An illustration of writing and envelope cases by Mechi & Bazin taken from the ‘Masterpieces of Industrial Art & Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862’ by J.B Waring.

An illustration of a writing table set by Mechi & Bazin taken from ‘The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862’.

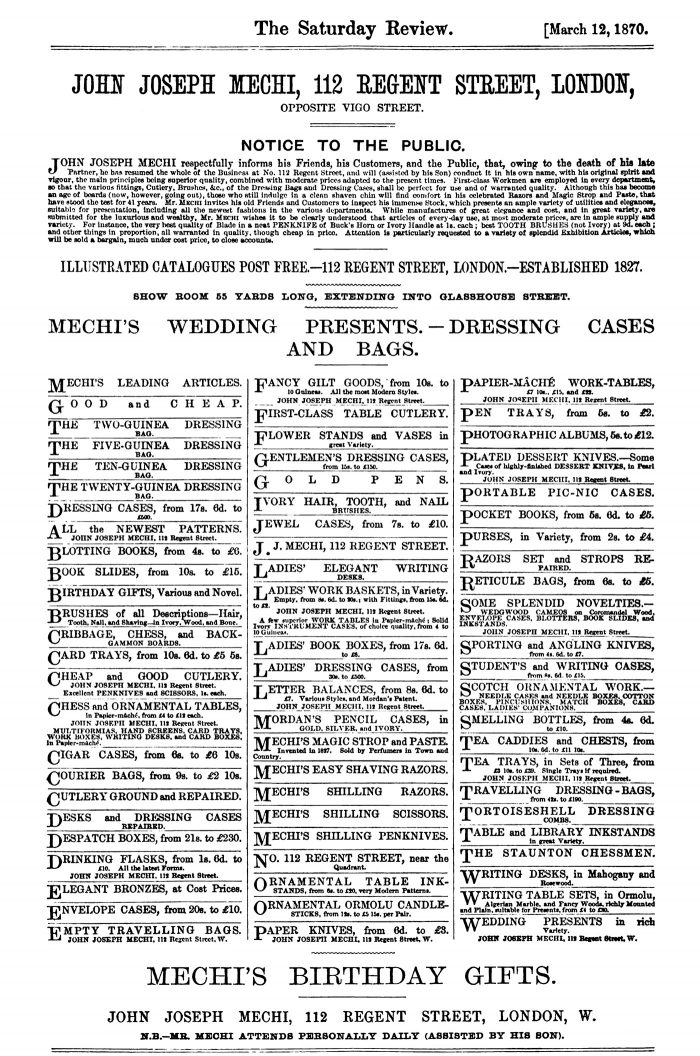

A Mechi advertisement taken from ‘The Saturday Review’ on March 12th 1870.

A Mechi & Bazin engraved brass manufacturer’s and retailer’s plate.

Monbro

Maltese born Georges Marie Paul Vital Bonifacio Monbro set up his business at 215 Rue de Beauregard (passage de la Boucherie), Paris in 1801. He quickly became recognised as a very skilled cabinetmaker (ébéniste), specialising in ’Nécessaire de Voyage’ boxes, and manufacturing for some of France’s most elite clientele.

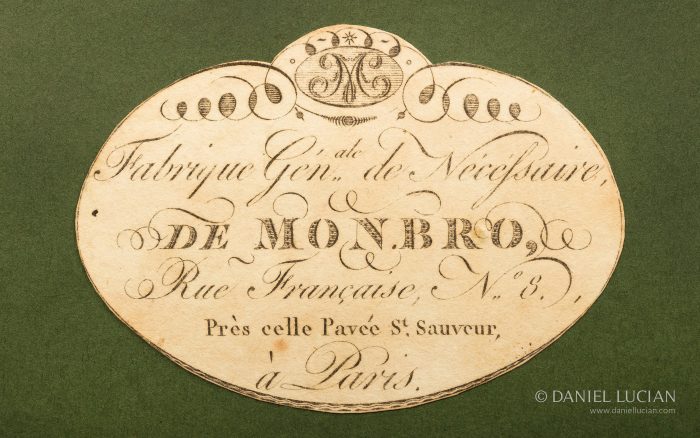

Over the next forty years Georges Monbro moved his business around Paris six times; 8 Rue Française in 1806, Rue Bourg-l’Abbé in 1810, 5 Rue du Cimetière-St.Nicolas in 1811, 44 Rue Basse-du-Rempart in 1832, 32 Rue Basse-du-Rempart, and finally 2 Rue Boudreau until his death in 1841.

His son, Georges Alphonse Bonifacio Monbro, took over the business in 1838 continuing the great reputation associated with the surname. Shortly after his father’s death, the business moved to 18 Rue Basse-du-Rempart. George Jr, known as Monbro Ainé (Monbro the eldest), exhibited at the Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie in 1844 and the Exposition Universelle in 1855. By this time, the business was also known as Monbro Fils Ainé, and their first international retail establishment had been opened (in 1852) at 370 Oxford Street, London. Their international success lead to the opening up of a further premises on London’s Frith Street in 1861.

By 1870, Monbro Fils Ainé were based at Rue de l’Arcade 56, Paris.

Paper manufacturer’s label belonging to Georges Monbro, from 1806.

Edwards

David Edwards established his cabinetmaking business in 1813 based at 84 St James’s Street, London. He remained at this address for about a year, before moving to 21 King Street, Bloomsbury, London.

Gaining a great reputation for the quality of his work, David Edwards was appointed, ‘Writing and Dressing Case manufacturer to his most gracious Majesty’, soon after King William IV came to the throne in 1830. READ MORE

Wells & Lambe

John Wells was a pocket-book manufacturer based at 34 Cockspur Street. After his death in 1804, his two children, Thomas and Elizabeth Wells, having both apprenticed with him, continued the business under the name of J. Wells & Co. READ MORE

Sampson Mordan & Co

Sampson Mordan was born in 1790. After some years of apprenticeship, he established his own business in 1815, and joined forces with John Isaac Hawkins by 1822; together they filed a patent for a metal pencil with an internal lead propelling mechanism. Unlike the pencil’s popularity and longevity, their business relationship did not last much longer, with Mordan buying out Hawkins soon-after. READ MORE

Lund

Thomas Lund established his business and warehouse at 57 Cornhill, London in 1804. Initially selling pens and quills, Thomas had expanded the business by about 1815 to include the manufacture of cutlery, writing boxes and other fancy items, taking an additional premises at 56 Cornhill. READ MORE

Aucoc

Taking over from Pierre-Dominique Maire, the highly respected ‘Nécessaire de Voyage’ manufacturer, the company of Aucoc was started by Jean-Baptiste Casimir Aucoc in 1821. Based at 154 Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, Casimir worked primarily a silversmith, his speciality also being in the manufacture of ‘Nécessaire de Voyage’ dressing and travelling cases. READ MORE

Index of French Makers and Retailers

Directory of French Nécessaire de Voyage and Nécessaire de Toilette manufacturers and retailers during the 18th and 19th Century. READ MORE

Index of Locksmiths

Directory of English locksmiths associated with antique dressing cases, antique toilet boxes, antique jewellery boxes and antique writing boxes. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Index of Silversmiths

Directory of English silversmiths associated with antique dressing cases. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Giroux

Maison Alphonse Giroux was established in 1799 by Francois-Simon-Alphonse Giroux, an art restorer, cabinet maker and one of the official restorers for the Notre Dame Cathedral. Based at 7, Rue du Coq-Saint-Honoré in Paris, the business initially started selling artist’s supplies, as well the products of his cabinetmaking work. The nature of the business soon expanded into the manufacturing and retailing of luxury goods and artwork, attracting the keen attention of french kings and members of the royal families. READ MORE

Bramah

Joseph Bramah started out by training as a cabinet-maker. In 1784, after attending some lectures on lock making, he patented his first lock and in the same year set up the Bramah Locks Company at 124 Piccadilly, London. READ MORE

Houghton & Gunn

William Houghton originally established his business in 1822. By 1841, he was based at 162 Bond Street, London. It wasn’t until 1868 that he went into partnership with Charles Henry Gunn. READ MORE

Halstaff & Hannaford

William Halstaff started his business in 1825 at 68 Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, London, later moving it in 1838 to 228 Regent Street, London as Halstaff & Co. READ MORE

Thornhill

The company of Thornhill can be traced back to a cutler named Joseph Gibbs in 1734, based at 137 Bond Street in London. By 1772, the business was in the hands of his son, James Gibbs, and in 1800, was renamed as Gibbs & Lewis. By 1805, the business was being run by John James Thornhill and John Morley, under the name of Morley & Thornhill. They moved to 144 New Bond Street, London in 1810. READ MORE

Index of British Makers and Retailers

Directory of British antique dressing case, antique toilet box, antique jewellery box and antique writing box manufacturers and retailers. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Chubb

The Chubb lock company was founded in 1818 by brothers, Charles and Jeremiah Chubb, at their premises on Temple Street, Wolverhampton. This was enabled by Jeremiah’s invention of the ‘Detector’ lock, winning him 100 Guineas in a government competition to create an un-pickable lock that could only be opened by its own key. READ MORE

Toulmin & Gale

The Toulmin & Gale company were originally established in 1735. By 1845, Joseph Toulmin and John Gale were in control of the company, based at 85-86 Cheapside, London. READ MORE

Howell, James & Co

The partnership of Howell and James was founded in 1819 by James Howell and Isaac James. Originally silk merchants and retail jewellers, they were based at 5, 7 and 9 Regent Street, London. READ MORE

Jenner & Knewstub

Established around 1856 by Frederick Jenner and Fabian James Knewstub, they were located at 33 St James’s Street, and then later in 1862, at 66 Jermyn Street, London. READ MORE

Hancock

Having been a partner in the company of Hunt & Roskell, Charles Frederick Hancock established his own business in 1849, based at 39 Bruton Street, London. By 1862 he had expanded to 38 Bruton Street and 152 New Bond Street, London. READ MORE

Leuchars

Leuchars was established at 47 Piccadilly, London in 1794 by James Leuchars. In 1820, the business moved to 38 Piccadilly shortly before James Leuchars died in 1823. READ MORE

Asprey

The Asprey company was originally founded as a silk printing business by William Asprey in 1781. Based from a shop in Mitcham, Surrey, William and his son Charles (I) soon started to retail luxury goods.

In 1841, Charles (I) formed a business partnership with his son-in-law, Francis Kennedy, a stationer based at 49 Bond Street, London. This partnership was to last until 1846, with Francis continuing on the business himself. By the end of 1847, Charles Asprey (I) and his son Charles (II) moved their business to 166 Bond Street, London. READ MORE

George Betjemann & Sons

In 1812 and at the age of 14, George Betjemann started apprenticing as a cabinet maker with his uncle, Gilbert Slater at his premises on Carthusian Street, London. In 1834, George then joined his father-in-law, William Merrick’s cabinet making business on Red Lion Street, Clerkenwell, London. George brought his sons, George William Betjemann (his eldest) and John Betjemann (grandfather of poet, Sir John Betjeman), to apprentice with him from 1848. READ MORE

Price On Application

Price On Application